President Trump, Vaccines, and the WHO

Upon the start of his new administration in 2025, President Trump signed an executive order to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO).

“The United States noticed its withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2020 due to the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China, and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states. In addition, the WHO continues to demand unfairly onerous payments from the United States, far out of proportion with other countries’ assessed payments. China, with a population of 1.4 billion, has 300 percent of the population of the United States, yet contributes nearly 90 percent less to the WHO.”

The WHO was founded in 1948, and for decades the United States of America has been a top contributor to the WHO. During the 2022-2023 biennium, the USA alone provided $1.284 billion to the WHO.

Much like criticisms of American health agencies’ failure to notify the public of discoveries this library has made at zero taxpayer cost (e.g., the FDA’s failure to notify the American public it updated the package insert for Valproate products to list ‘autism’ as a consequence since 2011), one might wonder whether a $1.284 billion dollar investment in the WHO has yielded any ROI.

An ‘investment’ is the proper term to view contributions the USA has made to the WHO over the years.

However, the returns we look for are not monetary; the ROI we’ve been expecting is American health.

Given that autism incidence rates have steadily increased since the very creation of the WHO in 1948, given that chronic illnesses in the USA has risen, given that health agencies in the USA under supposed guidance from the WHO have failed to guide American health in the proper directions, it is not inappropriate to say not only has the recent $1.284 billion dollar investment of the 2022-2024 biennium been utterly wasteful, but one may question altogether whether retroactive years of funding have truly yielded any returns.

Autism incidence rates have steadily increased, not decreased, in spite of generous contributions to the WHO by the USA.

President Trump previously attempted to exit the WHO in 2020, however, this decision was reversed by the Biden administration in 2021.

In recent public statements, President Trump apparently remains unsure whether exiting the WHO was the right decision. At a rally in Las Vegas, Nevada earlier this year in 2025, he stated “Maybe we would consider doing it again. I don’t know. Maybe we would have to clean it up a little bit.”

While many have called for withdrawal from the WHO and expect President Trump to remain firm in his decision, others ring the alarm.

Time magazine, for example, hails the WHO’s efforts in reducing illnesses through the world. A recent article by Time states, “The WHO was instrumental in coordinating the eradication of smallpox and is now working to eliminate polio.”

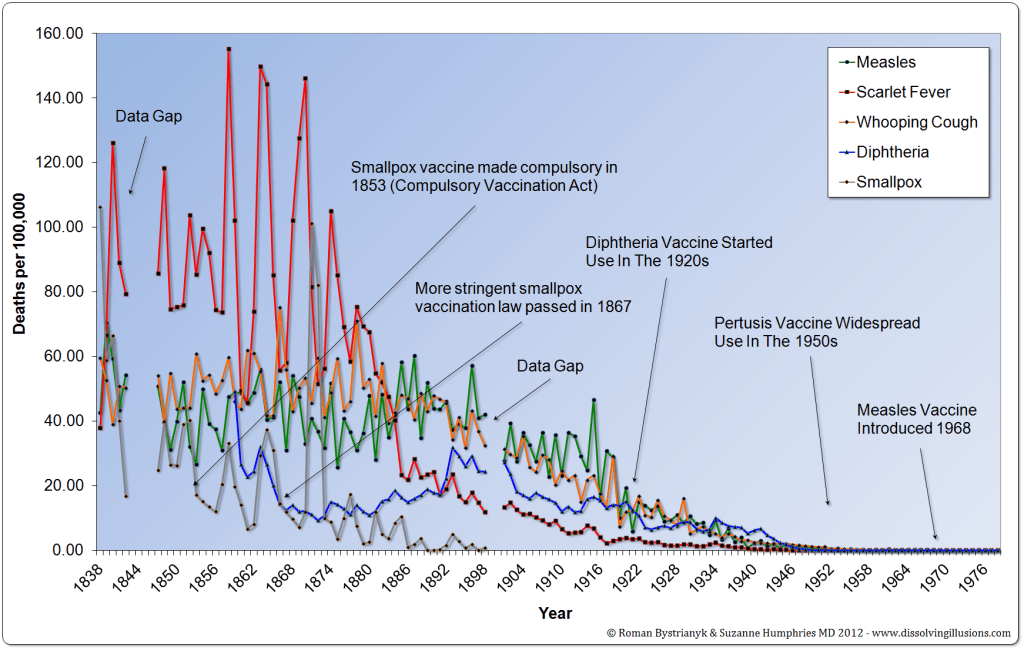

The prevailing consensus among those who follow mainstream media is that the eradication of various illnesses around the world came through worldwide vaccine administration and that the WHO has played an important role in this matter.

Is this a true statement though?

The WHO was established in 1948.

Measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diphtheria, and smallpox deaths in England and Wales had already declined to less than 20 per 100,000 by 1922 (Graph 1). In all cases, declines in mortality rates occurred prior to the introduction of vaccines and before the establishment of the WHO in 1948.

In the United states, deaths per 100,000 for measles, scarlet fever, typhoid, whooping cough, and diptheria had already declined to less than 5 deaths per 100,000 by 1936 which is twelve years before the WHO was established in 1948 (Graph 2). Once again, steep declines in mortality rates occurred prior to the introduction of various vaccines and before the WHO was established.

Do vaccines really “save lives”?

Did the World Health Organization play any role in the reduction of mortality rates of these diseases?

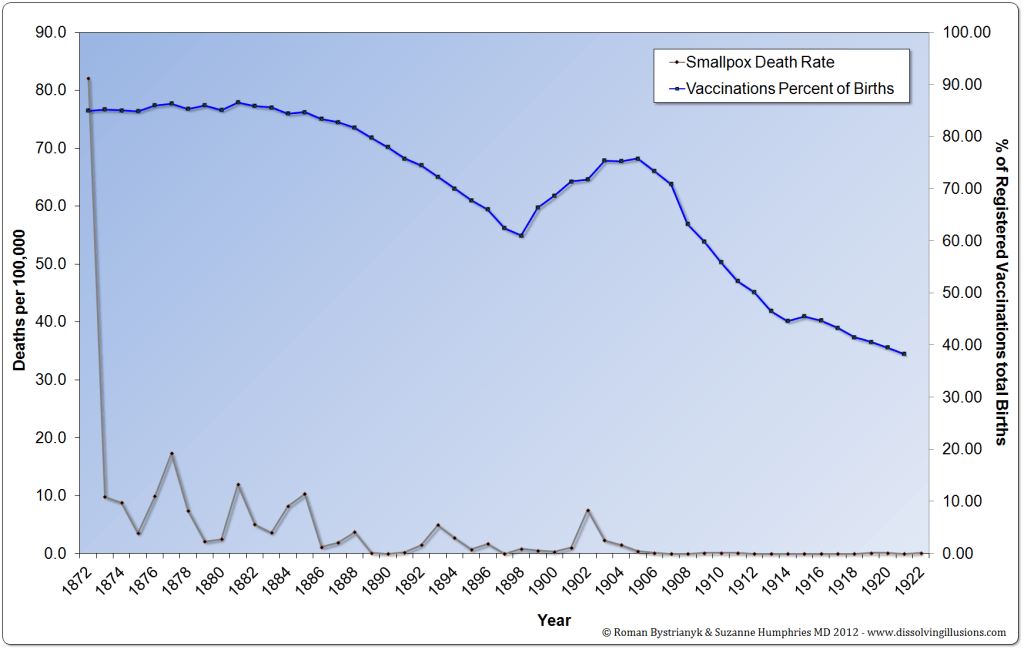

Available data from 1872 through 1922 indicates vaccines were unrelated to the decline in smallpox death rates in England and Wales.

In order to show a temporal correlation between increased smallpox vaccination rates and a decrease in mortality rates, the lines should meet and cross in opposite directions to show that as smallpox vaccine coverage rates have increased, smallpox death rates have decreased. However, the data does not; smallpox mortality rates decline in spite of a decrease in smallpox vaccine coverage rates across the 50 year time period (Graph 3).

Is the WHO given too much credit for reducing mortality of various illnesses worldwide that had declined prior to the WHO’s creation?

Are vaccines provided undeserved credit for reducing mortality of various illnesses worldwide that had declined prior to their introduction?

And let us not forget people can and do get polio from vaccines.

The CDC and the WHO themselves acknowledge people can and do get polio from vaccines.

The CDC has a page dedicated to education on vaccine-derived polio, acknowledging a polio case in New York in 2022 came from a vaccine.

In a 2022 article published by the WHO, the WHO also acknowledges the spread of vaccine-derived polio in the UK, Ireland, and America.

Vaccine-derived illnesses is a taboo topic among individuals who have been spoon-fed pharmaceutical propaganda; it’s a paradox to the way we view vaccines altogether.

How is a population supposed to protect themselves from a disease such as polio when the disease can mutate from a vaccine -and this is admitted in the aforementioned WHO article- to infect others?

The WHO article states: “Vaccine-derived poliovirus is a well-documented type of poliovirus that has mutated from the strain originally contained in the oral polio vaccine (OPV). The OPV contains a live, weakened form of poliovirus. On rare occasions, when replicating in the gastrointestinal tract, OPV strains genetically change and may spread in communities that are not fully vaccinated against polio, especially in areas where there is poor hygiene, poor sanitation, or overcrowding. Further changes occur as these viruses spread from person to person. The lower the population immunity, the longer this virus survives and the more genetic changes it undergoes. In very rare instances, the vaccine-derived virus can genetically change into a form that can paralyze – this is what is known as a vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV). “

It is unclear how much to blame vaccines themselves may be for “outbreaks” that are blamed on unvaccinated individuals, when the real culprit could be disease mutations arising out of vaccine administration. The logical fallacy is clear in the WHO’s statements: unvaccinated individuals can get polio through a genetic alteration from the oral polio vaccine itself.

In 2023, a measles “outbreak” in Maine turned out to be vaccine-strain derived as was confirmed by official CDC documents obtained by Informed Consent Action Network due to FOIA request.

How many disease “outbreaks” have occurred through the decades as a consequence of vaccine-derivation?

How are unvaccinated individuals at fault for being infected for a mutated vaccine-derived disease that originated from a vaccine to begin with?

Vaccine-Derived Disease Mutations and Genetic Mutations from Vaccines -What is the directionality of the relationship?

If the World Health Organization acknowledges a disease can mutate from a vaccine, what are the implications in light of this library’s discovery that not a single vaccine has ever been evaluated for mutagenic or carcinogenic potential?

Not a single vaccine on the market has undergone mutagenic and carcinogenic potential safety tests.

Lack of mutagenic and carcinogenic potential safety tests means the CDC never conducted safety tests to determine if a single dose or cumulative doses of vaccines can mutate genes to increase genetic susceptibility to other diseases known to man, including cancers. The evidence is publicly available on all vaccine package inserts typically in the Non-Clinical Toxicology section that the vaccine never went through safety testing for genetic mutations or increased risk of cancers.

Given the lack of mutagenic and carcinogenic safety tests for all vaccines, how does this impact our understanding of how diseases can mutate via vaccine administration?

In other words, are vaccines mutating genes that then result in disease mutation itself? This would be an interesting area for future research…albeit, perhaps not a welcome line of research for vaccine manufactures and stakeholders.

Do vaccines really save lives?

Importantly, the World Health Organization has never requested the CDC to conduct mutagenic or carcinogenic safety tests on vaccines to improve the safety of vaccines.

Why?

Are vaccines mutating genes, and are diseases also mutating as a consequence? Does the disease mutate first, and then mutate genes?

What is the direction of that relationship?

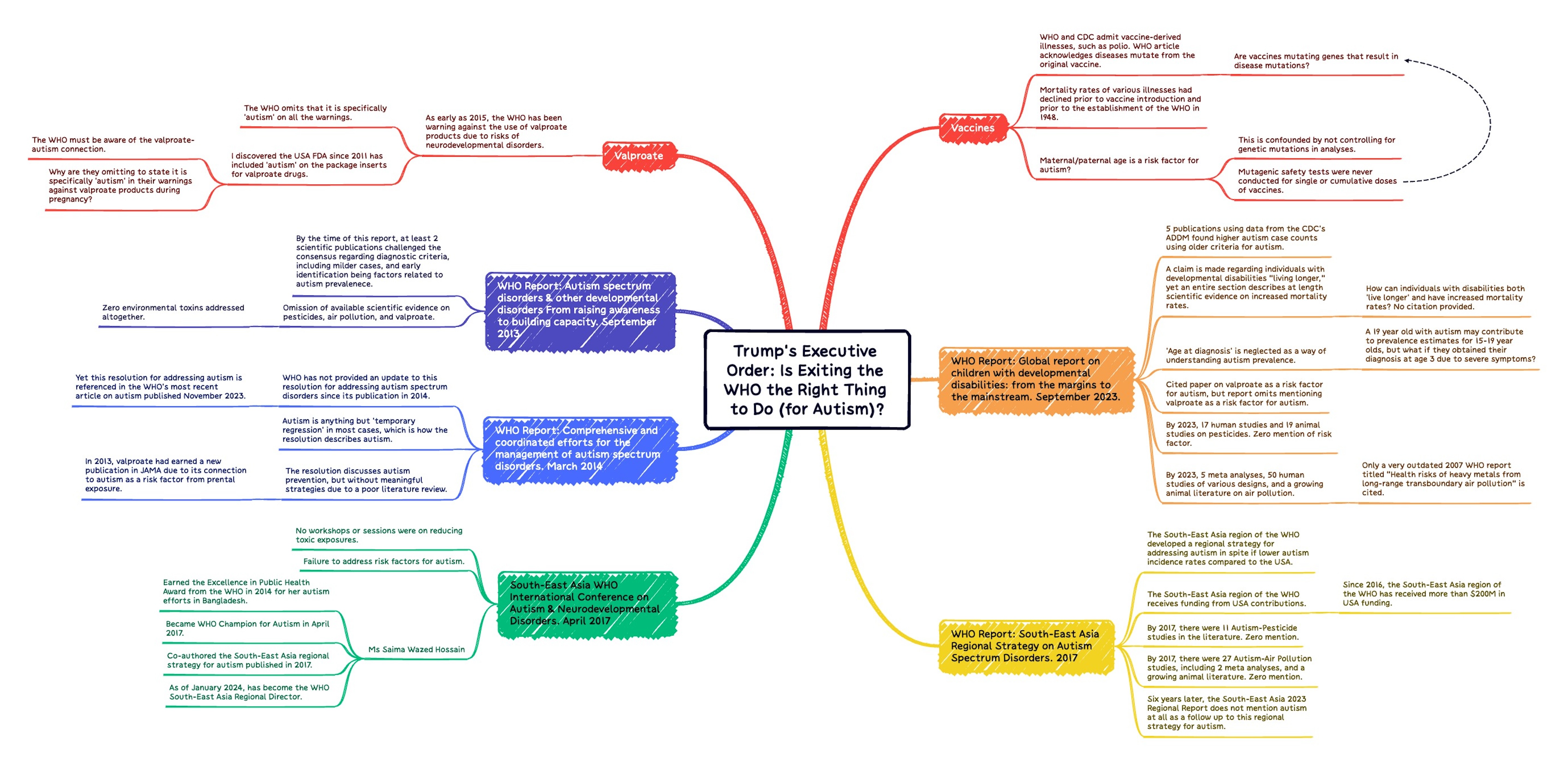

Autism and the World Health Organization

Within the domain of autism, President Trump’s executive order to withdraw from the WHO brings to light discussion regarding the WHO’s efforts surrounding autism.

In 2023, the WHO published its most recent report on neurodevelopmental disorders: “Global report on children with developmental disabilities: from the margins to the mainstream” which addresses multiple developmental disorders, such as developmental motor coordination disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism.

Surprisingly, the WHO has not filed a comprehensive report on autism spectrum disorders alone since 2014 which leaves the world with an outdated literature review of autism.

The WHO’s 2023 report focuses on multiple neurodevelopmental disorders, not just autism.

Given increasing autism incidence rates now at 1 in 30 in America, it is heavily arguable that autism deserves a complete and isolated review of the literature and it’s own extended analysis conducted by the WHO considering the USA was one of it’s largest contributors.

Has the WHO left autism in America ignored and neglected?

Let us now review the specific documents the WHO has published on neurodevelopmental disorders to answer this question.

Surprisingly, the WHO has scarcely published any reports on neurodevelopmental disorders through the years.

Only the following documents on neurodevelopmental disorders could be identified in WHO’s archives:

- Autism spectrum disorders & other developmental disorders From raising awareness to building capacity. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 16-18 September 2013

- Comprehensive and coordinated efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders. Sixty-Seventh World Health Assembly. A67/17. Provisional agenda item 13.4. 21 March 2014

- WHO South-East Asia Regional Strategy on Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2017

- International Conference on Autism & Neurodevelopmental Disorders Thimphu, Bhutan, 19–21 April 2017 (Summary Report)

- Global report on children with developmental disabilities: from the margins to the mainstream. September 15, 2023.

On the WHO website, the most recent article on autism was published nearly two years ago November 2023.

It was surprising to see that the WHO has not published an updated literature review in their addressing of the rising autism epidemic, and the November 2023 article proudly cites the 10 year old and outdated 2014 resolution by the Secretariat. A measly 4 citations are provided in the WHO’s November 2023 article on autism and 3 of the citations focus on berating Andrew Wakefield -the Wakefield matter is outdated by 2 decades as the evidence has continued to pile up regarding vaccines and autism, yet many continue to believe this matter is the sole-basis for the autism-vaccine debate.

Nevertheless, why is the WHO on their most recent November 2023 article citing the 2014 “Comprehensive and coordinated efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders”?

Does the WHO not intend to publish an updated review of the autism literature, which has only grown exponentially?

The WHO’s citing of the 2014 report in their November 2023 article, as well as the WHO’s board overview of developmental disabilities in their September 2023 report, is a strong sign that priority is not being given to autism spectrum disorders.

If ever there was a time for the WHO to have acted under influence of financial contributions, it would’ve been for autism considering the USA is dealing with exponentially rising autism rates and has been one of the WHO’s largest financial contributors.

But perhaps money doesn’t talk after all.

The USA’s $1.284 billion contribution to the WHO was for naught.

WHO Report: “Autism spectrum disorders & other developmental disorders From raising awareness to building capacity” World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 16-18 September 2013

This was the WHO’s first published report on autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. There are several major flaws in this first report that are not corrected in subsequent reports.

Quote: “There are many possible explanations for this apparent increase in prevalence, including improved awareness, expansion of diagnostic criteria, better diagnostic tools and improved reporting. Other likely contributors comprise changes in diagnostic practices, including expansion of developmental screening, increased diagnosis and diagnostic substitution, whereby children who in the past would have been identified as having an intellectual disability are now being diagnosed with ASDs. Some of the increase in prevalence may also be the result of diagnostic accretion, whereby some people are given more than one diagnosis, and hence the prevalence appears higher, even though the same number of people is affected.”

- Major Criticism: By the time this report was published in 2013, a study published in 2002 using a diverse population in California, USA found that changes in diagnostic criteria could not account for increases in autism incidence across the study period [1].

Another 2009 publication could only account for 188 out of 700 percent change in autism incidence across the study period when considering changes to diagnostic criteria, including milder cases, and early identification [2].

Quote: “Developmental disorders, including ASDs, are disorders of early brain development, and although the cause of ASDs remains unknown, some specific prenatal, perinatal and environmental risk factors, such as high maternal and paternal age and specific gene mutations, have been identified. It is unclear what role these risk factors may play in the reported increase in prevalence.”

- Major Criticism: This library has contributed the discovery that no vaccine has ever been evaluated for mutagenic potential. The CDC never conducted safety tests to determine if vaccines mutate genes, and thereby never conducted tests examining if any genetic mutations arising out of single or cumulative dose exposure to vaccines impact autism risk via parental genetic mutations impacting autism risk in the offspring, or childhood genetic mutations impacting autism risk in the child.

Additionally, while maternal and paternal age may be a factor, if genetics studies do not control for (zero/low vs high) genetic mutations arising out of cumulative exposure to toxins across a lifespan (not just vaccines, but other toxins impacting genetic mutations across the lifespan), is this possibility statistically controlled for?

For example, if a man works on farmland and has daily exposure to pesticides for 10 years, how do genetic mutations arising out of pesticide exposure impact risk of autism in that man’s offspring? Can we solely blame his getting older as impacting autism risk? Without accounting for genetic mutations, the ‘age’ variable in the autism literature (and dare I say, ‘any other scientific literature…’?) is confounded.

Can genetic mutations be ruled out from maternal/paternal age as a risk factor for autism, so as to isolate the effect of age alone?

Or is the true culprit genetic mutations due to toxic exposures?

Quote: “Highlighting that there is no valid scientific evidence that childhood vaccination leads to autism spectrum disorders.”

- Major Criticism: This is scientifically challenged on many fronts, including studies that do find an association, questionable methodologies by studies that claim no association, and lack of mutagenic testing of vaccines. Available and growing evidence has been compiled in this library.

Overall Critique: The report has zero mentions of pesticides, air pollution, valproate, or any other toxin with a scientific research paper linking it to autism risk.

Since the report was published in 2013, some of these additional literatures were still in their early stages with few publications.

However, there were published studies at the time that could have been addressed.

This resolution for addressing autism spectrum disorders is cited in the WHO’s November 2023 article on autism, which is the last posting (report or otherwise) in regards to autism that the WHO has published.

The WHO Resolution for addressing autism is replete with errors.

Quote: “Characteristic features of the onset include delay in the development or temporary regression in language and social skills and repetitive stereotyped patterns of behaviour.”

- Major Criticism: ‘Temporary regression’ is incorrect; for many individuals with autism, the regression in adaptive skills can result in lifelong deficits in language and social skills that impact the individual and their family’s quality of life. It is anything but ‘temporary’ in most cases.

Quote: “Available epidemiological data conclusively prove that there is no evidence of a causal association between measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and autism spectrum disorders. Previous studies suggesting this causal link were found to contain serious methodological flaws. There is also no evidence that any childhood vaccine increases the risk of a child developing an autism spectrum disorder. WHO has commissioned reviews of the potential association between [thimerosal] preservative and aluminium adjuvants contained in inactivated vaccines and the risk of developing autism spectrum disorders. The results firmly support the conclusion that no such association exists.”

- Major Criticism:

- DeStefano (2004) scandal- In 2014, CDC senior scientist Dr. William Thompson via his attorney published a press release testifying to the omission of the association between MMR and African American males [16]. Hooker (2018) re-analyzed the dataset and found 3.86 odds of autism for African American boys who were vaccinated with MMR prior to 36 months [17].

Schultz et al. (2008)- found an association between sequelae after the MMR vaccine and increased risk of autism [18].

Madsen et al. (2002) is a popular study cited to claim the MMR-autism vaccine debate was settled due to their conclusion of no association. However, the study has been the subject of scientific scrutiny, such as autism being diagnosed at age 5 in Denmark at the time, resulting in many children who had not received an autism diagnosis by the endpoint of the study. This and other evidence regarding questionable methodologies of studies that claim no association between vaccines and autism has been compiled in this library under a section titled “Studies That Claim No Significant Relationship between Vaccines and Autism.”

- DeStefano (2004) scandal- In 2014, CDC senior scientist Dr. William Thompson via his attorney published a press release testifying to the omission of the association between MMR and African American males [16]. Hooker (2018) re-analyzed the dataset and found 3.86 odds of autism for African American boys who were vaccinated with MMR prior to 36 months [17].

Quote: “…to implement strategies for health promotion and prevention of life-long disabilities associated with autism spectrum disorders, by: developing and implementing multisectoral approaches for the promotion of health and psychosocial well-being of persons with autism spectrum disorders, the prevention of associated disabilities and co-morbidities…”

- Major Criticism: Zero mention of efforts to prevent life-long disabilities through reduction of exposure to environmental toxins associated with autism. The section ambiguously states they would like to prevent autism, but does not address the means. In other words, it cheerleads without actually leading prevention efforts.

Quote: “The Secretariat has contributed to compiling data on autism spectrum disorders through the following projects. A global survey on resources for child mental health was conducted in 2005, and in 2011 a similar survey of child, adolescent and maternal mental health resources was undertaken in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Their findings revealed that few resources are directed towards management of autism spectrum disorders or even mental health care in general. Moreover, the scarce resources that are available are often inefficiently used and inequitably distributed. The Mental Health Gap Action Programme’s Evidence Resource Centre contains systematic reviews of the evidence for effective interventions for prevention and management of developmental disorders including autism spectrum disorders.”

Overall Criticism: Once again, there is no mention of a ‘comprehensive and coordinated’ effort to address any toxins associated with autism. There is zero mention of environmental toxins in this resolution by the WHO Secretariat. The defense of vaccines given the WHO’s heavy funding from the vaccine industry is expected. However, by 2014, there were growing literatures on pesticides, air pollution, and valproate that were unacknowledged.

The failure to address environmental toxins is surprising, as well as the exclusion of mentioning valproate as a risk factor for autism considering the year prior in 2013 there was a publication in the prestigious journal JAMA that found prenatal valproate exposure was associated with increased risk of autism [13].

After this report in 2014, nearly a decade went by before the WHO’s next publication on neurodevelopmental disorders in 2023.

The South-East Asia region of the WHO published a report addressing autism spectrum disorder in 2017 (addressed next).

However, the WHO as an integrative whole (non-region specific) has not conducted an updated literature review and report of the autism literature, and has not updated their resolution for addressing autism spectrum disorders since this was published in 2014.

WHO Report: WHO South-East Asia Regional Strategy on Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2017

This report is classified as the South-East Asia regional strategy for addressing autism [14]. This report is a lone document amongst others: no other regional strategy reports for addressing autism could be identified.

Given increasing autism incidence rates in the USA, why hasn’t the WHO conducted a regional strategy specifically for the USA?

As with previous WHO publications on autism thus far, the report falls short on various fronts.

Major Criticisms:

- Failure to Address Pesticide literature- by 2017, there were 11 Autism-Pesticide studies in the literature.

- Failure to Address Air Pollution literature- by 2017, there were 27 studies, including 2 meta analyses, and a growing animal literature.

- Failure to Address Vaccines- the report defends vaccines, which is expected. By 2017, there was also growing evidence of the connection between vaccines and autism/autism symptoms from both studies using data from the CDC’s Vaccine Safety Datalink as well as external data sources.

- Failure to Address Valproate- as early as 2015, the WHO has been warning against the use of valproate products due to risks of neurodevelopmental disorders (this will be addressed in-depth later). This report fails to address valproate.

- Quote: “To implement strategies to minimize disabilities associated with ASD…”

- Major Criticism: to minimize disabilities associated with ASD, a comprehensive review of the literature on environmental toxins and disabilities associated with ASD (such as ADHD) is necessary, and this report fails to include other literatures or remotely mention environmental toxins.

- Quote: “A study conducted in Bangladesh by the National Institute of Mental Health in 2009 revealed the prevalence of autism to be 0.8% for children 5–14 years old. Data from the National Statistical Office of the Higher Education Commission of Thailand revealed that in 2010, the estimated prevalence of autism in children was 0.6%.”

- Major Criticism: These are autism prevalence rates from available data for South-East Asia for 2009-2010, which is less than 1 in 100.

By contrast, the CDC reported autism prevalence rates of 1 in 68 in the USA for 2010.

Why did the South-East Asia region obtain a “regional strategy” for addressing autism when they had lower autism incidence rates than the USA?

Suffice it to say autism incidence rates in the USA have increased, based upon reports from the CDC.

Yet the USA remains without its own regional strategy.

- Major Criticism: These are autism prevalence rates from available data for South-East Asia for 2009-2010, which is less than 1 in 100.

Overall criticism: the report echoes previous and future WHO publications that cheerlead for autism by advocating for better support systems, leadership, and governance to manage autism. The report ironically calls for better research on autism yet fails to address the available literatures on pesticides, air pollution, and valproate associated with autism.

In regards to why the South-East Asia region obtained a regional strategy for addressing autism but not other regions and none thereafter, the evidence points toward the designation of Ms Saima Wazed as a ‘WHO Champion’ as well as a WHO International Autism Conference for the South-East Asia region in April 2017.

Ms Saima Wazed Hossain was designated WHO Champion for Autism in April 2017 due to her previous regional autism efforts in South-East Asia. She later co-authored the South-East Asia regional strategy for autism after previously earning the Excellence in Public Health Award from the WHO in 2014 for her autism efforts in Bangladesh. As of January 2024, Saima Wazed has become the WHO South-East Asia Regional Director.

Did the South-East Asia region obtain a regional strategy report due to Ms. Wazed’s previous efforts surrounding autism?

The publication of the South-East Asia regional strategy for addressing autism in November 2017 occurred a few months after the South-East Asia region of the WHO had an International Autism Conference in April of the same year [15].

A review of the summary report for the WHO South-East Asia International conference earns it the same criticisms as the regional strategy report itself: utter failure in recognizing available scientific literatures to mitigate risk of autism due to environmental exposures. None of the workshops or sessions delved into the topic of reducing toxic exposures, let alone addressing environmental factors as a risk factor.

The disregard for vaccines as a contributing factor for autism was expected from both the South-East Asia autism conference and their regional strategy report.

It was not expected that growing literatures on pesticides, air pollution, and valproate would be neglected, as this constitutes an utter failure of a scientific literature review.

A question worth considering is if the South-East Asia region perhaps earned a regional strategy report for addressing autism due to financial contributions to the WHO.

The answer would appear to be no.

The USA has been a top contributor to the WHO for decades.

In fact, a review of WHO contributions during the 2016-2017 biennium reveals that the South-East Asia WHO region actually received $34.5M in contributions that came from USA funding of the WHO.

Since 2016, the South-East Asia region of the WHO has received more than $200M in USA funding. The 2022-2023 biennium reveals the largest contribution toward the South-East Asia region of the WHO, totaling $90.6M from USA funding.

A series of follow up questions are in order?

- How much in USA funding was spent on the South-East Asia International Autism conference in 2017?

- How much in USA funding was spent on the South-East Asia regional strategy for addressing autism spectrum disorders in 2017?

- Why is the USA funding the WHO to develop regional strategies and conferences to address autism spectrum disorders in South-East Asia, yet the WHO hasn’t provided the USA with regional strategies and conferences for addressing autism spectrum disorders considering higher autism incidence rates in the USA?

- Considering the USA spends more on healthcare than any other high income country, considering the USA ranks low in various health outcomes compared to many other countries, considering Americans have shorter life expectancies and higher rates of death and diseases compared to other many nations, why are high amounts of USA contributions toward the WHO being funneled toward improving health in other countries?

- Once again, considering higher autism incidence rates in the USA in 2017, why did the South-East Asia region of the WHO develop a regional strategy report for autism, but not the USA?

Notwithstanding the fact that the South-East Asia regional strategy for autism fails to address relevant literatures on toxins associated with autism, perhaps it’s a good thing zero WHO funding was spent on developing a USA regional strategy for managing autism or holding a conference in the USA. It would’ve been a waste of time and money without proper attention given to environmental toxins which the conference and regional strategy report ignored.

It is odd that in spite of the South-East Asia developing a regional strategy for addressing autism since 2017, seven years later the report of the Regional Director for the South-East Asia WHO region does not mention autism at all. A small section of the report is devoted to developmental disabilities and summarizes efforts that are already becoming widespread: early identification and community/parent support.

If the South-East Asia WHO region has a regional strategy for addressing autism, why not provide the public an update seven years later in the 2024 publication of the region’s efforts?

Scientific literatures on environmental toxins have only grown in that time period.

Does the WHO not intend to address any scientific literature on toxins associated with autism?

Just what exactly are the WHO’s priorities concerning autism?

Global report on children with developmental disabilities: from the margins to the mainstream. September 15, 2023.

This is the WHO’s most recent report on developmental disabilities and is supposed to contain the most updated review of the literature to inform the world on neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Surprisingly, in spite of being the latest review of the literature, the report falls short in several key areas.

Quote: “…increases in the estimated prevalence of developmental disabilities may indicate better identification and/or be due to people with developmental conditions living longer. As such, the incidence of developmental disabilities may remain the same, but increases in detection or longevity will increase prevalence over time”

- Major Criticism: Previously mentioned in criticisms of the 2013 report were the 2002 and 2009 publications that found that changes in diagnostic criteria, early identification, and including milder cases could not account for increases in autism incidence [1, 2].

Now by 2023 there are at least 5 publications spanning the years 2014-2021 using data from the CDC’s Autism Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) that found higher autism case counts using OLDER criteria for autism [3-7].

Maenner et al. (2014) concluded, “Based on these findings, ASD prevalence per 1000 for 2008 would have been 10.0 (95% CI, 9.6–10.3) using DSM-5 criteria compared with the reported prevalence based on DSM-IV-TR criteria of 11.3 (95% CI, 11.0–11.7). Autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates will likely be lower under DSM-5 than under DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, although this effect could be tempered by future adaptation of diagnostic practices and documentation of behaviors to fit the new criteria.” [3]

Baio et al. (2018) concluded, “Overall, ASD prevalence estimates based on the new DSM-5 case definition were very similar in magnitude but slightly lower than those based on the historical DSM-IV-TR case definition. Three of the 11 ADDM sites had slightly higher case counts using the DSM-5 framework compared with the DSM-IV-TR. Implementation of the new DSM-5 case definition had little effect on the overall number of children identified with ASD for the ADDM 2014 surveillance year.” [4]

Maenner et al. (2020) concluded, “In the subset of children whose records also were reviewed using ADDM Network DSM-IV-TR ASD criteria, the DSM-IV-TR criteria classified 2% more ASD cases than DSM-5 criteria.” [5]

Shaw et al. (2020) concluded, “Using DSM-5 criteria, prevalence of ASD was lower compared with using DSM-IV-TR criteria at one site (New Jersey) of four sites that reviewed ≥50% of records using both criteria (Table 3). Overall prevalence at the four sites was 16.3 per 1,000 children aged 4 years using DSM-5 criteria and 18.9 per 1,000 children aged 4 years using DSM-IV-TR (prevalence ratio: 0.9; Cohen’s kappa = 0.83).” [6]

Maenner et al. (2021) concluded, “We found little difference in the overall prevalence estimates based on the previous and new ADDM Network case definitions for 2014, and a slightly lower prevalence based on the new ADDM Network case definition for 2016.” [7]

In total, 7 publications scientifically contradict claims that changes to diagnostic criteria account for increases in autism incidence rates.

Oddly, later publications using data from the ADDM do not make additional comparisons between newer and older diagnostic criteria for autism [8-12]. Why omit additional comparisons? It is odd that later studies omit statistical comparisons between older case definitions of autism versus newer ones, yet

Major Criticism: In regards to the statement that individuals with developmental disabilities are “living longer,” this was an odd statement to make given the WHO report devotes an entire section on discussing poorer health outcomes and increased mortality rates among individuals with developmental disabilities.

Quote: “Children, young people and adults with developmental disabilities have a higher risk of premature death (122, 123). In a cohort of 306 children with epilepsy or cognitive, vision, hearing or motor impairments identified from a Developmental disabilities in focus 19 baseline screening of 10 218 children aged 6–9 years in rural Kenya, mortality rates were three to four times higher than controls (124). A longitudinal population based study in rural eastern Uganda reported an excessively high risk of premature death in children with cerebral palsy, especially in those with severe motor impairments or malnutrition (125). Children with intellectual disabilities have significantly higher rates of avoidable, treatable and preventable mortality when compared with the general population (126– 129). The most common underlying, avoidable causes of mortality include epilepsy, choking and respiratory infections (129). Injuries are also associated with increased risk of mortality in persons with autism and in persons with ADHD (121, 128).”

The WHO does not provide scientific studies to support the claim that improvements in longevity of those with developmental disabilities is impacting prevalence rates.

Additionally, the logic is flawed: how can individuals with disabilities have both increased mortality AND live longer?

The claim requires a research study assessing morality rates per year for those with diagnosed developmental disabilities for perhaps at least a 30 year timespan to analyze if there is a reduction in mortality rates among individuals with disabilities.

No such study appears to have been conducted yet, and the WHO report does not mention such a study. Where is the scientific support for that claim?

The morbid reality: if mortality rates are not decreasing among individuals with developmental disabilities yet prevalence rates are increasing, then more individuals with developmental disabilities are dying in present years.

Quote: “While individual prevalence studies and peer reviewed meta-analyses provide one set of estimates of prevalence, the IHME uses data synthesis and mathematical modelling to produce GBD estimates of the prevalence of specific conditions by age group, gender and location, prevalence being defined as the total number of cases in the population (Global Health Data Exchange database).”

- Major Criticism: This WHO report defines ‘prevalence’ as the total number of cases in a population. Nothing wrong with that: we want to know how many cases of a developmental disorder are present within an age group.

However, this fails to tell us when the individual was diagnosed with the disorder, which could point us in the direction of exposure to toxins leading to a subsequent diagnosis.

For example, adults with autism will be grouped by their age (e.g., a 15 year old with a diagnosis of autism in the medical system at the time of the study will be grouped into the 15-19 year old prevalence estimate) but if they were diagnosed at a young age (e.g., they were actually diagnosed at 5 years old) this fails to inform the public regarding the actual age at diagnosis -which fails to point researchers in the direction of sensitive periods in the lifespan where toxic exposures lead to a diagnosis in the first place.

However, can researchers accurately interpret prevalence rates without cross-referencing the age at diagnosis?

A 2024 JAMA publication I criticized made such an omission in data collection.

Can we accurately interpret prevalence estimates without considering the age at which every individual received the diagnosis?

How does ‘age at diagnosis’ change our understanding of a 19 year old with autism who contributed to the 15-19 year old prevalence estimate of a study, when in fact they were diagnosed at 3 years old due to the severity of their autism symptoms already present at that age?

‘Age at diagnosis’ is a variable that could point us closer in regards to when the delay in development began (e.g., did parents notice missed milestones at 6 months; was there regression at 1 year, etc.).

Quote: “Animal, human cell and epidemiological studies suggest that a wide range of environmental risks impact neurodevelopment (61–75).”

- Major Criticism: Citation 64 under the section “Developmental disabilities in focus” is an article devoted to discussing the impact of various toxins on neurodevelopment, directly addressing valproate, lead, methylmercury, and other factors.

Surprisingly, the WHO omitted direct mention of valproate in this report.

Valproate is important to include as a risk factor for autism in the WHO’s 2023 report consider I discovered that since 2011 the USA-FDA listed ‘autism’ on Valproate products and did not properly inform the public of the update via the drug safety communication.

In other reports and statements (addressed next), the WHO has warned against the use of valproate products during pregnancy due to impacts on neurodevelopment.

But why omit the valproate-autism connection in this report on developmental disabilities when they acknowledge valproate-neurodevelopmental disorder risks in other reports?

Major Criticism: No citations on the environmental risks impacting neurodevelopment mention pesticides or air pollution.

Failure to address growing Pesticides literature- 17 human studies and 19 animal studies on pesticides as a risk factor for autism published by the time of this report in 2023.

Failure to address growing Air Pollution literature- 5 meta analyses, 50 human studies of various designs, and a growing animal literature published by the time of this WHO report. An outdated 2007 WHO report titled “Health risks of heavy metals from long-range transboundary air pollution” is cited.

Major Criticism: The entire collection of studies cited by the 2023 WHO report on environmental risk factors associated with autism are an extremely poor representation of the available literature and omit significant toxins.

Quote: “Means to mitigate risks related to environmental health include limiting heavy metals such as cadmium, lead and mercury in the environment. Minimizing exposure to lead by, for instance, eliminating old lead paints and inhalation exposure can prevent lead poisoning and neurodevelopmental impairment in children.”

- Major Criticism: In terms of meaningful strategies for reducing environmental toxic exposures to mitigate risk of developmental disabilities, these two sentences are the ONLY recommendations provided in the WHO report.

No other strategies for addressing environmental toxic exposures are addressed, which is not unexpected given the report fails to address additional available literatures.

Needless to say, vaccines as a risk factor for autism remain unaddressed in the WHO 2023 report. From a standpoint of vaccine safety advocacy which calls for improvements in vaccine safety tests, the lack of saline-placebo controlled clinical trials and the lack of mutagenic and carcinogenic potential safety tests for vaccines on the market should be enough to make anyone question whether scientific studies that claim vaccines are ‘safe’ are in fact true.

Overall criticism: the most updated WHO report on developmental disabilities fails to address growing available scientific literatures on multiple environmental toxins associated with autism, and thus, cannot provide the world at large strategies for mitigating autism risk via reducing toxic exposures.

Is the WHO’s priority solely on managing autism after diagnoses?

Is there no priority given on managing autism prevention?

Before summarizing the entirety of the WHO’s efforts on autism spectrum disorders, we will now turn our attention to another matter: Valproate.

In December 2024, I announced my discovery and contribution to the Valproate-Autism literature that the FDA did not inform the public via a drug safety communication in 2011 of the addition of ‘autism’ as an adverse effect for offspring of mothers who took Depakote/Depakene products during pregnancy.

It is presently unknown how proper announcement by the FDA would have impacted autism incidence rates around the USA or world.

To this day, most Americans and countries that fund the WHO remain unaware of the valproate-autism connection.

However, it is interesting to discover that technically the World Health Organization has been warning against valproate products during pregnancy due to risk of neurodevelopmental disorders to offspring as early as 2015 via their Mental Health Gap Action Programme:

“Patients’ comorbidities and childbearing potential also have to be considered when recommending a newer antiepileptic medication in those with medication resistant convulsive epilepsy as some antiepileptic medications are associated with a higher risk of teratogenicity and worst neurodevelopmental outcomes than others (e.g., valproic acid).”

No specific mention of autism itself being the neurodevelopmental outcome in their May 2015 WHO mhGAP Guideline Update.

In January 2023, a month after the WHO’s second joint meeting on vaccine safety, they published an addendum to their Mental Health GAP guidelines reminding against the use of valproate products during pregnancy “because of the high risk of birth defects and developmental disorders in children exposed to valproic acid (sodium valproate) in the womb.”

In this January 2023 addendum, the WHO fails to mention it is specifically ‘autism’ that is the neurodevelopmental disorder that is the concern.

Considering the FDA has added ‘autism’ on the package insert for Valproate products since 2011, is the WHO’s failure to specifically state that it is ‘autism’ that is the neurodevelopmental disorder at risk justifiable?

Over 100 countries implement the WHO’s Mental Health GAP (mhGAP) guidelines which discuss valproate for the treatment of bipolar disorder within the context of mental health. In these guidelines, autism is only discussed within the context of caregiver training, management of autism in the community, and treatment options. The prevention of autism via minimizing exposure to environmental toxins associated with autism is not addressed on the WHO’s mhGAP.

On May 2, 2023 the WHO issued an official statement regarding valproate, “Valproic acid (sodium valproate) should not be prescribed to women and girls of childbearing potential because of the high risk of birth defects and developmental disorders in children exposed to valproic acid (sodium valproate) in the womb.”

For a third time, the WHO omits specifically which neurodevelopmental disorders are the ones at risk.

Later in 2023, the WHO’s November 2023 mhGAP publication echoes previous warnings: “Valproic acid (sodium valproate) is not recommended in women and girls of childbearing potential owing to the high risk of birth defects and neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed to valproic acid (sodium valproate) in the womb.”

Now for at least a fourth time the WHO omits it is ‘autism’ that is the neurodevelopmental disorder at risk.

Why the omission?

It is worth noting that the WHO’s first mhGAP publication in 2008 does not mention valproate products at all, and therefore no comments are made on neurodevelopmental risks. Va

Given the increasing incidence rates of autism in the USA, is such an omission of ‘autism’ being the specific disorder that is at risk due to prenatal valproate exposure ethical?

A series of follow up questions are in order:

- Does the WHO know about the Valproate-Autism connection as noted on FDA package inserts and in the available scientific literature?

- If the WHO knows about the Valproate-Autism connection…

- Are they deliberately omitting this knowledge from their statements, addendums, and guidelines to countries around the world?

- What are the consequences for omitting ‘autism’ as this significant detail?

- Are there legal consequences to this?

- Are there ethical implications to this?

- How did the WHO first come to know about the Valproate-Autism connection?

- Did the USA FDA inform selected officials at the WHO about the package insert for Valproate products?

- Is the WHO versed in the Valproate-Autism literature and purposefully omitting this from their reports?

- In what year did the WHO first learn about the Valproate-Autism connection?

- Have they known since 2011 when the package inserts for valproate were updated in the USA to list ‘autism’?

Given the aforementioned regarding the WHO’s omission of ‘autism’ when referring to risks of valproate products during pregnancy, can it be concluded the WHO is intentionally covering this evidence?

A Summary of the WHO’s Autism Failures

Given the World Health Organization has failed in the following areas concerning autism spectrum disorders:

- Failed to address 17 human studies and 19 animal studies on Pesticides as a risk factor for autism published by 2023

- Failed to address 5 meta analyses, 50 human studies of various designs, and a growing animal literature on Air Pollution as a risk factor for autism published by 2023

- Failed to inform the public ‘autism’ is the neurodevelopmental disorder at risk due to prenatal valproate exposure as a consequence of both available scientific literature on valproate-autism as well as the FDA’s inclusion of ‘autism’ on the package insert for valproate products since 2011

- Failed to address growing evidence autism-vaccine evidence post-Wakefield matters, including:

- my discovery of the lack of mutagenic or carcinogenic potential safety tests for vaccines before market release, which poses a scientific challenge to the CDC’s claim that ‘vaccines do not cause autism’ from a mutagenic potential forefront,

- methodological flaws in studies that claim to find no association between vaccines and autism,

- studies both within and outside the CDC’s Vaccine Safety Datalink database that find an association,

- the CDC’s failure to furnish research studies to support claims regarding vaccines when FOIA’d by Informed Consent Action Network

- Failed to address scientific evidence regarding the decline in mortality rates of various illnesses prior to the introduction of vaccines

- Failed to provide the USA an individualized regional strategy for addressing autism spectrum disorders, which should have been a high priority considering:

- The USA has historically been one of the WHO’s largest financial contributors

- The USA has experienced massive increases in autism incidence rates as a country

- The USA had higher autism incidence rates than South-East Asia at the time of their regional strategy report

- Failed to address scientific evidence of at least 5 studies using data from the CDC’s ADDM that find older diagnostic criteria for autism found higher case counts

- Failed to address scientific evidence from at least 2 studies concluding changes in diagnostic criteria, early identification, and mild case inclusion could not account for increases in autism incidence

- Failed to update the WHO resolution for addressing autism spectrum disorders since 2014

- Failed to provide a comprehensive report on autism, specifically, since 2013

this researcher concludes that President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the WHO was the correct decision.

The World Health Organization’s priorities regarding autism are not on autism prevention, but focus on creating governance, infrastructure, and workforce to manage autism. Further reliance on the WHO under the influence of poor literature reviews with almost zero strategies for mitigating risk of toxic exposures would constitute further scientific negligence toward addressing this important matter.

It is unclear at the present time why the WHO is omitting important literatures such as pesticides, air pollution, and valproate concerning neurodevelopmental disorders. Conflicts of interest that may contribute toward negligence of scientific literature, while important, are beyond the scope of this analysis, as this review has focused exclusively on evaluating the proficiency of the WHO’s literature review on environmental toxins associated with autism based upon available scientific evidence to answer the question: has the WHO conducted a thorough review of the literature to provide a well-rounded approach toward mitigating risk of autism?

The answer, in my review, is no.

Exiting the WHO, based upon their reports, yields little impact toward autism spectrum disorders and could perhaps free up resources internally within the USA toward addressing factors the WHO has neglected.

This analysis is provided with zero conflicts of interest: this library has never received funding and is independently researched by a Board Certified Behavior Analyst employed full-time in early intervention Applied Behavior Analysis services for children with autism.

References

- Byrd et al. (2002). Report to the Legislature on the Principal Findings from The Epidemiology of Autism in California: A Comprehensive Pilot Study. https://www.dds.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/DSInfo_ReportToTheLegislature_200221017.pdf

- “The observed increase in autism cases cannot be explained by a loosening in the criteria used to make the diagnosis.

- Some children reported by the Regional Centers with mental retardation and not autism did meet criteria for autism, but this misclassification does not appear to have changed over time.

- Children served by the State’s Regional Centers are largely native born and there has been no major migration of children into California that would explain the increase in autism.”

- Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 20(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181902d15

- “In summary, the incidence of autism rose 7- to 8-fold in California from the early 1990s through the present.

Quantitative analysis of changes in diagnostic criteria, inclusion of milder cases, and an earlier age at diagnosis suggests that these factors probably contribute 2.2-fold, 1.56-fold, and 1.12-fold increases in autism, and hence cannot fully explain the magnitude of the rise in autism.”

- “In summary, the incidence of autism rose 7- to 8-fold in California from the early 1990s through the present.

- Maenner, M. J., Rice, C. E., Arneson, C. L., Cunniff, C., Schieve, L. A., Carpenter, L. A., Van Naarden Braun, K., Kirby, R. S., Bakian, A. V., & Durkin, M. S. (2014). Potential impact of DSM-5 criteria on autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates. JAMA psychiatry, 71(3), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3893

- “Based on these findings, ASD prevalence per 1000 for 2008 would have been 10.0 (95% CI, 9.6–10.3) using DSM-5 criteria compared with the reported prevalence based on DSM-IV-TR criteria of 11.3 (95% CI, 11.0–11.7).

- Autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates will likely be lower under DSM-5 than under DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, although this effect could be tempered by future adaptation of diagnostic practices and documentation of behaviors to fit the new criteria.”

- Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Robinson Rosenberg, C., White, T., Durkin, M. S., Imm, P., Nikolaou, L., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Lee, L. C., Harrington, R., Lopez, M., Fitzgerald, R. T., Hewitt, A., Pettygrove, S., … Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 67(6), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1

- “Overall, ASD prevalence estimates based on the new DSM-5 case definition were very similar in magnitude but slightly lower than those based on the historical DSM-IV-TR case definition. Three of the 11 ADDM sites had slightly higher case counts using the DSM-5 framework compared with the DSM-IV-TR.”

- “Implementation of the new DSM-5 case definition had little effect on the overall number of children identified with ASD for the ADDM 2014 surveillance year.”

- “Overall, ASD prevalence estimates based on the new DSM-5 case definition were very similar in magnitude but slightly lower than those based on the historical DSM-IV-TR case definition. Three of the 11 ADDM sites had slightly higher case counts using the DSM-5 framework compared with the DSM-IV-TR.”

- Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Robinson Rosenberg, C., Lee, L.-C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., Hewitt, A., Esler, A., Hall-Lande, J., Poynter, J. N., Hallas-Muchow, L., Constantino, J. N., Fitzgerald, R. T., Zahorodny, W., Shenouda, J., Daniels, J. L., Warren, Z., Vehorn, A., Salinas, A., Durkin, M. S., & Dietz, P. M. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

- “In the subset of children whose records also were reviewed using ADDM Network DSM-IV-TR ASD criteria, the DSM-IV-TR criteria classified 2% more ASD cases than DSM-5 criteria.”

- Shaw, K. A., Maenner, M. J., Baio, J., Washington, A., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., White, T., Robinson Rosenberg, C., Constantino, J. N., Fitzgerald, R. T., Zahorodny, W., Shenouda, J., Daniels, J. L., Salinas, A., Durkin, M. S., & Dietz, P. M. (2020). Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years—Early Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, six sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6903a1

- “Using DSM-5 criteria, prevalence of ASD was lower compared with using DSM-IV-TR criteria at one site (New Jersey) of four sites that reviewed ≥50% of records using both criteria (Table 3).

Overall prevalence at the four sites was 16.3 per 1,000 children aged 4 years using DSM-5 criteria and 18.9 per 1,000 children aged 4 years using DSM-IV-TR (prevalence ratio: 0.9; Cohen’s kappa = 0.83).”

- “Using DSM-5 criteria, prevalence of ASD was lower compared with using DSM-IV-TR criteria at one site (New Jersey) of four sites that reviewed ≥50% of records using both criteria (Table 3).

- Maenner, M. J., Graves, S. J., Peacock, G., Honein, M. A., Boyle, C. A., & Dietz, P. M. (2021). Comparison of 2 Case Definitions for Ascertaining the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among 8-Year-Old Children. American journal of epidemiology, 190(10), 2198–2207. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab106

- “We found little difference in the overall prevalence estimates based on the previous and new ADDM Network case definitions for 2014, and a slightly lower prevalence based on the new ADDM Network case definition for 2016. In addition, we found no clear differences by sex or race/ethnicity.

There was essentially no difference by median age at first evaluation, median age at first diagnosis, and proportion of children with intellectual disability. Both case definitions failed to identify children who had been identified only by the other method. The new case definition identified some children who were missed by the previous case definition because the child’s evaluations or records could not be obtained. Additionally, a small proportion of cases identified using only the new definition had ASD diagnoses from a community provider who evaluated the child but the ADDM Network clinicians overruled the diagnosis. Likewise, the previous case definition classified some cases by reviewing evaluations and overruling the community clinician who concluded that the child did not have ASD.”

- “We found little difference in the overall prevalence estimates based on the previous and new ADDM Network case definitions for 2014, and a slightly lower prevalence based on the new ADDM Network case definition for 2016. In addition, we found no clear differences by sex or race/ethnicity.

- Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., Nguyen, R. H. N., Pierce, K., Zahorodny, W., Hudson, A., Hallas, L., Mancilla, K. C., Patrick, M., Shenouda, J., Sidwell, K., DiRienzo, M., Gutierrez, J., Spivey, M. H., Lopez, M., Pettygrove, S., Schwenk, Y. D., Washington, A., & Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

- Neglected to compare DSM-4 and DSM-5 differences

- Hughes, M. M., Shaw, K. A., DiRienzo, M., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Hall-Lande, J., Wiggins, L., Zahorodny, W., Singer, A., & Maenner, M. J. (2023). The Prevalence and Characteristics of Children With Profound Autism, 15 Sites, United States, 2000-2016. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 138(6), 971–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549231163551

- Neglected to compare DSM-4 and DSM-5 differences

- Hughes, M. M., Shaw, K. A., Patrick, M. E., DiRienzo, M., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Hudson, A., Spivey, M. H., DaWalt, L. S., Salinas, A., Schwenk, Y. D., Lopez, M., Baroud, T. M., & Maenner, M. J. (2023). Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Diagnostic Patterns, Co-occurring Conditions, and Transition Planning. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 73(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.12.010

- Neglected to compare DSM-4 and DSM-5 differences

- Shaw, K. A., Bilder, D. A., McArthur, D., Robinson Williams, A., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Warren, Z., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., Patrick, M., Zahorodny, W., Green, K. K., Hall-Lande, J., Lopez, M., Mancilla, K. C., Nguyen, R. H. N., Pierce, K., Schwenk, Y. D., Shenouda, J., Sidwell, K., Vehorn, A., DiRienzo, M., Gutierrez, J., Hallas, L., Hudson, A., Spivey, M. H., Pettygrove, S., Washington, A., & Maenner, M. J. (2023). Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7201a1

- Neglected to compare DSM-4 and DSM-5 differences

- Patrick, M. E., Hughes, M. M., Ali, A., Shaw, K. A., & Maenner, M. J. (2023). Social vulnerability and prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP). Annals of epidemiology, 83, 47–53.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.04.009

- Neglected to compare DSM-4 and DSM-5 differences

- Christensen, J., Grønborg, T. K., Sørensen, M. J., Schendel, D., Parner, E. T., Pedersen, L. H., & Vestergaard, M. (2013). Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA, 309(16), 1696–1703. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.2270

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2017). WHO South-East Asia regional strategy on autism spectrum disorders. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259505. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2017). International conference on autism and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/259504. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- DeStefano, F., Bhasin, T. K., Thompson, W. W., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., & Boyle, C. (2004). Age at first measles-mumps-rubella vaccination in children with autism and school-matched control subjects: a population-based study in metropolitan atlanta. Pediatrics, 113(2), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.2.259

- Hooker, B.S. (2018). Reanalysis of CDC Data on Autism Incidence and Time of First MMR Vaccination. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons, 23, 4. https://www.jpands.org/vol23no4/hooker.pdf

- Schultz, S. T., Klonoff-Cohen, H. S., Wingard, D. L., Akshoomoff, N. A., Macera, C. A., & Ji, M. (2008). Acetaminophen (paracetamol) use, measles-mumps-rubella vaccination, and autistic disorder: the results of a parent survey. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 12(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361307089518