I was under the impression that JAMA was one of the best journals in the world. Well, maybe less so given that vaccine researchers can only dream of having a paper implicating vaccines in autism diagnoses published in the journal. Nevertheless, given that the authors of a recent publication on incidence of autism fail to mention entire literatures on toxins associated with autism such as pesticides and air pollution when discussing their findings regarding increasing rates of autism [1], I can only wonder what un-rigorous standards JAMA researchers are held to when conducting a literature review in preparation for a publication.

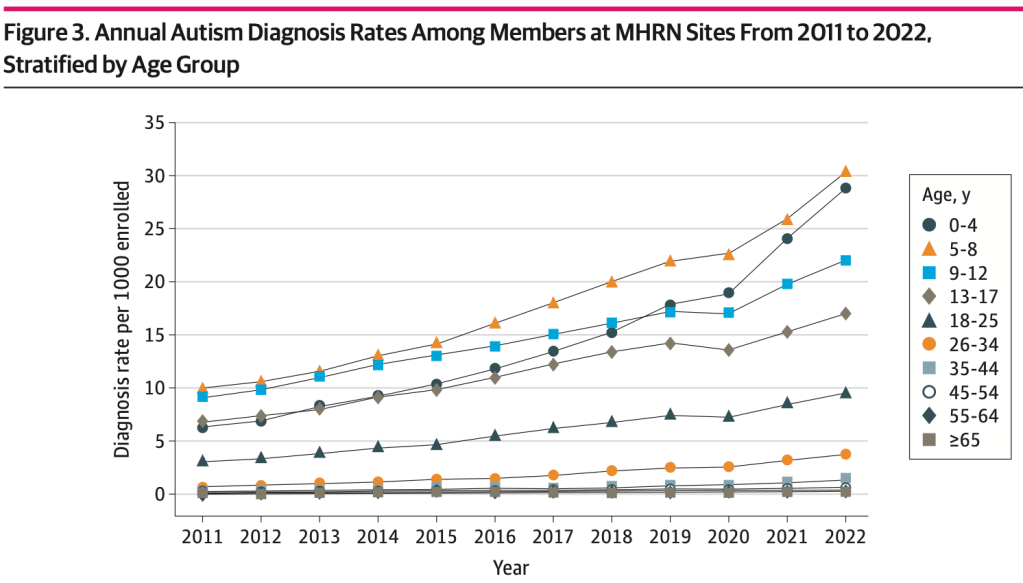

The new publication examines increases in autism diagnoses across the years 2011 through 2022 and reports increases among young adults, female children and adults, and children from some racial or ethnic minority groups (Grosvenor et al., 2024).

No surprise there.

There’s a cocktail of toxins in the environment and the literatures on them are further behind in understanding their connection to autism than where they should be. [Shout out to the researchers examining environmental toxins whose studies have contributed to this library. Boy does this JAMA paper make you all look good.]

I would pose a question, however, regarding the neglect of these literatures…

Is it scientifically ethical to publish a paper on autism rates without at least mentioning studies on toxins that are associated with autism?

Can the publication be used to misinform the public via undermining the impact of various toxins on increases in autism diagnostic rates over the years?

Is the neglect of such literatures scientific negligence?

Is the omission of mention of such literatures unethical?

A major concern is how the lack of citing studies on toxins associated with autism may impact researcher perceptions regarding the association between various toxins and autism, thereby impacting growing interest in those literatures, thereby impacting continued efforts for further research within those literatures, thereby impacting funding for such research.

I cannot shake the feeling having myself extracted many of the significant findings of multiple literatures and continuing the journey presently through the Acetaminophen literature, that the neglect to mention these literatures constitutes scientific negligence.

But who is to blame?

I am morbidly reminded of the time that world-renowned podcast “HubermanLab Podcast” had a Stanford professor as a guest to talk about autism. Surprisingly, the Stanford professor also catastrophically failed to mention any environmental toxins associated with autism.

A Commentary on the Huberman Lab Podcast with Dr. Karen Parker

Unfortunately, this speaks to a degree of bias regarding the undermining of toxins associated with autism and the continued push for a narrative that states “we’re just getting better at catching and diagnosing autism,” a bias driven by studies such as this one that fail to mention such literatures, and a notion that has been challenged by various studies.

Key issues with the paper

- Pesticide literature is unethically unaddressed

- Air Pollution literature is unethically unaddressed

- Vaccine literature is unethically unaddressed

- Well, it might be considered a miracle if vaccines contributing to autism incidence was mentioned in this JAMA paper, but one can hope.

- Other toxins associated with autism unethically unaddressed, such as valproate, acetaminophen, and toxic heavy metals.

- Citing Hansen et al. (2015), the authors state that changes in prevalence are due to diagnosis definitions [2]. However, there are quite some issues with this assertion:

- There were 6 human studies and 2 animal studies on autism-pesticides published prior to this paper [4-9].

- There were 17 air-pollution studies on humans published prior to their study [10-26].

- Having neglected growing literatures on pesticides and air pollution prior to their publication, can the authors be sure changes in diagnostic criteria are the sole reason for changes in autism incidence without factoring exposure to toxins?

- Hansen et al. explains a 60% increase of autism incidence in children born from 1980 through 1991 in Denmark, but this limited time frame is hardly generalizable due to the increase in the number of vaccines on the childhood vaccine schedule beginning in 1986, which has only skyrocketed since then.

- Grosvenor et al. authors contradict themselves: The limitations section of the same paper states “the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 codes in 2015 was previously found to have little to no impact on ASD diagnosis rates.”

- This is inconsistent with what is stated in the introduction of the paper, which is that “Hypothesized reasons for prevalence increases include changes to developmental screening practices, diagnosis definitions, policies, and environmental factors as well as increased advocacy and education.

- Publications on autism prevalence from the Center for Disease Control have found that that DSM-IV-TR case definitions classified more autism cases (2-4%) than DSM-5 criteria [27-28]. Can researchers truly state changes in diagnostic criteria (case definitions) amount to changes in autism incidence over hundreds of percentage points, when data from the CDC has indicated DSM-IV criteria amounted to slightly more cases?

- Citing Zeidan et al. (2022), the JAMA authors acknowledge environmental factors contributing to rising rates of autism. However, there are multiple issues with the paper they cited:

- Like Hansen et al. (2015), these authors fail to remotely mention the pesticides and air pollution literatures in their study, which 7 years later included an even greater number of publications.

- Zeidan et al. (2022) state “an increase in prevalence over time is taken as a reflection of change in exposure to environmental risk factors,” but provide no citations for these environmental risk factors to guide other researchers toward literatures on toxins.

- The researchers push the narrative regarding “significant improvements in early identification of the condition, which in part, accounts for higher prevalence rates over time.” However, can they truthfully draw this conclusion without mentioning growing literatures on toxins associated with autism?

- Major flaw in not examining trends by ‘Age at Diagnosis‘

- In the limitations section of the paper, the research authors clearly state ‘age at diagnosis’ was not used in the analysis to analyze trends.

- This is a major limitation: were adults with a diagnosis of autism grouped into older age groups in spite of receiving an autism diagnosis at a young age?

- This could bias the results of the study in that adults with an autism diagnosis may be assumed to have been diagnosed late in life, supporting the authors assertions that “we are getting better at diagnosing autism.” Prenatal and early life are sensitive time periods for exposure to toxins with literatures behind, and it goes without saying exposure to such toxins may constitute early age of diagnosis of autism. How many adults in the sample had an early age diagnosis of autism? Did this result in:

- A bias leading to inflated adult prevalence?

- A bias leading to underestimated childhood prevalence?

- Age at diagnosis is arguably THE most important variable to consider within the context of environmental exposure to toxins resulting in a subsequent autism diagnosis. Not including this variable to analyze trends renders the findings of the study quite useless unless we correlate age at diagnosis to age at exposure to toxins.

- Major limitation by not factoring severity of autism symptoms

- Within the context of ‘age at diagnosis,’ equally important is to correlate the severity of autism symptoms to age at diagnosis.

- One testable hypothesis being that the severity of autism symptoms is correlated with a younger age at diagnosis.

- Out of medical necessity to access autism services, many parents would take in their child at a young age for an evaluation once developmental milestones are not being met, especially if the severity of autism symptoms are beginning to impact the family’s quality of life.

- The severity and number of toxic exposures at various points in early life, its relationship to age at diagnosis, as well as the severity of autism symptoms is another testable hypothesis that would shed light on what exactly is contributing to increases in autism incidence.

It is noteworthy to state that in spite of such limitations, the study authors find that autism prevalence increased 352% among 0-4 year olds between 2011 and 2022. This can only be indicative of prenatal and early life exposure to various toxins.

Similarly, autism rates increased 450% among 25-34 year olds between 2011 and 2022. However, the findings in this age group, and even older age groups, are suspect without consideration for severity of autism symptoms that would necessitate an early age of diagnosis so the parents may access various autism services for their child. Without understanding ‘age at diagnosis,’ these findings are difficult to interpret.

It is not the intention here to undermine those adults who indeed obtained an autism diagnosis out of medical necessity to obtain care for their needs. However, in such cases it is not untruthful to state that the severity of autism symptoms may not have been so profound as to require an early age of diagnosis for access to autism services -something more and more parents are only too willing to obtain due to increased autism awareness around services for young children with autism.

Counterarguments

- If the researchers sole aim was to study autism incidence, they wouldn’t need to address literatures on toxins.

- The authors do cite faulty papers to explain that increases in autism incidence are due to changes in diagnosis definition. Thus, in doing so, they are attempting to explain why autism rates are increasing.

- Because they are attempting to explain why through various citations, they should have included mention of other literatures.

- Thus, it is scientifically negligent to not address these literatures and draw sole attention to views regarding changes in diagnostic criteria or screening methods.

- It isn’t the researchers responsibility to conduct a complete literature review on other toxins if the study is only analyzing autism incidence rates.

- True. But it’s the ethical responsibility to at least mention that various toxins are associated with autism diagnosis, even if they don’t include that entire literature. How hard is it to read and cite a couple of papers on pesticides and air pollution?

- These researchers may have been unaware of the growing literatures on pesticides and air pollution and due to this did not mention them.

- This is not an excuse. Either the authors failed as researchers to inform themselves on these other literatures, or intentional negligence has occurred in this publication.

For the aforementioned reasons, it is stated clearly to the scientific community that failing to remotely mention growing literatures on toxins associated with autism in a paper examining increases in autism rates is the epitome of scientific negligence.

At worst, this was unethical and a move to undermine alternative explanations for increases in autism rates.

References

- Grosvenor, L. P., Croen, L. A., Lynch, F. L., Marafino, B. J., Maye, M., Penfold, R. B., Simon, G. E., & Ames, J. L. (2024). Autism Diagnosis Among US Children and Adults, 2011-2022. JAMA network open, 7(10), e2442218. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.42218

- Hansen, S. N., Schendel, D. E., & Parner, E. T. (2015). Explaining the increase in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: the proportion attributable to changes in reporting practices. JAMA pediatrics, 169(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1893

- Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696

- Roberts, E. M., English, P. B., Grether, J. K., Windham, G. C., Somberg, L., & Wolff, C. (2007). Maternal residence near agricultural pesticide applications and autism spectrum disorders among children in the California Central Valley. Environmental health perspectives, 115(10), 1482–1489. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10168

- Cheslack-Postava, K., Rantakokko, P. V., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S., Surcel, H. M., McKeague, I. W., Kiviranta, H. A., Sourander, A., & Brown, A. S. (2013). Maternal serum persistent organic pollutants in the Finnish Prenatal Study of Autism: A pilot study. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 38, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2013.04.001

- Keil, A. P., Daniels, J. L., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2014). Autism spectrum disorder, flea and tick medication, and adjustments for exposure misclassification: the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) case-control study. Environmental health : a global access science source, 13(1),3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-13-3

- Shelton, J. F., Geraghty, E. M., Tancredi, D. J., Delwiche, L. D., Schmidt, R. J., Ritz, B., Hansen, R. L., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2014). Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environmental health perspectives, 122(10), 1103–1109. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307044

- Mullen, B. R., Khialeeva, E., Hoffman, D. B., Ghiani, C. A., & Carpenter, E. M. (2012). Decreased reelin expression and organophosphate pesticide exposure alters mouse behaviour and brain morphology. ASN neuro, 5(1), e00106. https://doi.org/10.1042/AN20120060

- Laugeray, A., Herzine, A., Perche, O., Hébert, B., Aguillon-Naury, M., Richard, O., Menuet, A., Mazaud-Guittot, S., Lesné, L., Briault, S., Jegou, B., Pichon, J., Montécot-Dubourg, C., & Mortaud, S. (2014). Pre- and postnatal exposure to low dose glufosinate ammonium induces autism-like phenotypes in mice. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 8, 390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00390

- Jung, C. R., Lin, Y. T., & Hwang, B. F. (2013). Air pollution and newly diagnostic autism spectrum disorders: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. PloS one, 8(9), e75510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075510

- Gong, T., Almqvist, C., Bölte, S., Lichtenstein, P., Anckarsäter, H., Lind, T., Lundholm, C., & Pershagen, G. (2014). Exposure to air pollution from traffic and neurodevelopmental disorders in Swedish twins. Twin research and human genetics : the official journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 17(6), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2014.58

- Windham, G. C., Zhang, L., Gunier, R., Croen, L. A., & Grether, J. K. (2006). Autism spectrum disorders in relation to distribution of hazardous air pollutants in the san francisco bay area. Environmental health perspectives, 114(9), 1438–1444. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9120

- Kalkbrenner, A. E., Daniels, J. L., Chen, J. C., Poole, C., Emch, M., & Morrissey, J. (2010). Perinatal exposure to hazardous air pollutants and autism spectrum disorders at age 8. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 21(5), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e65d76

- Volk, H. E., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Delwiche, L., Lurmann, F., & McConnell, R. (2011). Residential proximity to freeways and autism in the CHARGE study. Environmental health perspectives, 119(6), 873–877. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002835

- McCanlies, E. C., Fekedulegn, D., Mnatsakanova, A., Burchfiel, C. M., Sanderson, W. T., Charles, L. E., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2012). Parental occupational exposures and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(11), 2323–2334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1468-1

- Becerra, T. A., Wilhelm, M., Olsen, J., Cockburn, M., & Ritz, B. (2013). Ambient air pollution and autism in Los Angeles county, California. Environmental health perspectives, 121(3), 380–386. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205827

- Roberts, A. L., Lyall, K., Hart, J. E., Laden, F., Just, A. C., Bobb, J. F., Koenen, K. C., Ascherio, A., & Weisskopf, M. G. (2013). Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the children of Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Environmental health perspectives, 121(8), 978–984. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1206187

- Windham, G. C., Sumner, A., Li, S. X., Anderson, M., Katz, E., Croen, L. A., & Grether, J. K. (2013). Use of birth certificates to examine maternal occupational exposures and autism spectrum disorders in offspring. Autism research: official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 6(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1275

- Volk, H. E., Lurmann, F., Penfold, B., Hertz-Picciotto, I., & McConnell, R. (2013). Traffic-related air pollution, particulate matter, and autism. JAMA psychiatry, 70(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.266

- Volk, H. E., Kerin, T., Lurmann, F., Hertz-Picciotto, I., McConnell, R., & Campbell, D. B. (2014). Autism spectrum disorder: interaction of air pollution with the MET receptor tyrosine kinase gene. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 25(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000030

- Palmer, R. F., Blanchard, S., Stein, Z., Mandell, D., & Miller, C. (2006). Environmental mercury release, special education rates, and autism disorder: an ecological study of Texas. Health & place, 12(2), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.11.005

- Ming, X., Brimacombe, M., Malek, J. H., Jani, N., & Wagner, G. C. (2008). Autism spectrum disorders and identified toxic land fills: co-occurrence across States. Environmental health insights, 2, 55–59. https://doi.org/10.4137/ehi.s830

- Palmer, R. F., Blanchard, S., & Wood, R. (2009). Proximity to point sources of environmental mercury release as a predictor of autism prevalence. Health & place, 15(1), 18–24. Lewandowski, T. A., Bartell, S. M., Yager, J. W., & Levin, L. (2009). An evaluation of surrogate chemical exposure measures and autism prevalence in Texas. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A, 72(24), 1592–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390903232483https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.001

- Lewandowski, T. A., Bartell, S. M., Yager, J. W., & Levin, L. (2009). An evaluation of surrogate chemical exposure measures and autism prevalence in Texas. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A, 72(24), 1592–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390903232483

- Blanchard, K. S., Palmer, R. F., & Stein, Z. (2011). The value of ecologic studies: mercury concentration in ambient air and the risk of autism. Reviews on environmental health, 26(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh.2011.015

- Windham, G. C., Sumner, A., Li, S. X., Anderson, M., Katz, E., Croen, L. A., & Grether, J. K. (2013). Use of birth certificates to examine maternal occupational exposures and autism spectrum disorders in offspring. Autism research: official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 6(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1275

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020;69(No. SS-4):1–12. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

- Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Robinson Rosenberg, C., White, T., Durkin, M. S., Imm, P., Nikolaou, L., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Lee, L. C., Harrington, R., Lopez, M., Fitzgerald, R. T., Hewitt, A., Pettygrove, S., … Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 67(6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1