This section of the library shall be dedicated to commentaries on Children’s Health Defense content. Included below is not a summary of the content (I’ll leave that for you to check out), but rather my comments in terms of psychology, health, and human behavior. Whenever possible, I draw connections to autism as well. Most of my comments originally appear on Twitter/X, so be sure to follow on there.

Judge Refuses to Hear Expert Testimony on Tylenol Link to Autism, ADHD

The following is a developing commentary and analysis regarding a recent decision by New York District Judge Denise Cote regarding Tylenol and Autism in which she opined that there is not “admissible evidence” regarding a causal link between acetaminophen (Tylenol) and autism/ADHD, resulting in the exclusion of multiple expert opinions on the research literature.

Diagnosis vs. Symptoms

I remember with fondness one of my graduate school professors’ disregard toward the DSM, referring to it as an arbitrary collection of diagnoses that were “all made up,” alluding to the fact that they had no true biological basis but, rather, are an attempt to organize symptoms into structured criteria we can make sense out of -not to mention that it affects decisions and litigation surrounding healthcare. In reading Judge Cote’s opinions on the expert analyses, as well as the defendants’ counter arguments against them, the issue of “Diagnosis vs. Symptoms” is obvious. What is the importance, and the difference, of using diagnostic criteria versus symptoms in outcome measures? However, I contend that both types of outcome measures provide similar, valuable, and different information.

I agree with Dr. Baccarelli on the following point:

“Dr. Baccarelli claims that a shared Bradford Hill analysis is “appropriate” because the symptoms associated with deficits in cognition, communication, motor skills, self-regulation or social-emotional function “transcend diagnostic boundaries” and because ASD and ADHD are both categorized as NDDs in the DSM.” (page 65)

Since the creation of this library I’ve held to the notion that DSM criteria are simply that: criteria made by humans attempting to categorize and understand physiological and psychological processes to improve healthcare decision making. And let us not forget how many revisions the DSM has undergone, presently sitting on its 5th edition. What has not changed is how our human body expresses symptoms as a consequence of various environmental toxins -of which there are many new ones released into the environment each year.

That said, Judge Cote and the defendants did not fail to notice inconsistencies regarding the reliance on DSM criteria versus symptoms in the expert opinions regarding the literature on acetaminophen, and these are used in their counterarguments.

“Dr. Baccarelli’s assessment of a study’s

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK. Acetaminophen – ASD-ADHD Products. Denise cote, district judge. Page 65

use of a non-ADHD, non-ASD endpoint seems to depend on whether the study’s result supports his ultimate opinion about a causal connection with prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.”

For example, she points out that Dr. Baccarelli was inconsistent in his critique of the Laue (2019) study [12], of which he was one of the authors, which did not find an association between acetaminophen in meconium and a child’s intelligence scores. Dr. Baccarelli critiqued the study’s use of IQ as an assessment because IQ does not directly bear on ADHD or ASD criteria, yet does not extend that critique to Liew et al. (2016) which did find an association between maternal acetaminophen use and lower intelligence scores without using ADHD/ASD outcomes [11]. Judge Cote also points out this inconsistency within the context of the use of the transdiagnostic analysis performed by Dr. Baccarelli, who asserts that cognition is a deficit that justifies his transdiagnostic analysis, and that cognition and other symptoms “transcend diagnostic boundaries.”

Symptoms versus diagnostic criteria side for a moment, it is interesting to consider that the a study published in 2023 found that autism severity was associated with low IQ, and that the low IQ-autism relationship persisted even when excluding Fragile-X datasets [10], providing some genetic control. This new study perhaps adds weight to the study by Liew et al. (2019) that used IQ in their methods and found an association between lower intelligence scores and maternal acetaminophen use, and could add further understanding to the effect that acetaminophen may have on IQ and autism symptom severity, pending further research examining these relationships.

Returning to Judge Denise Cote, while her arguments surrounding Dr. Baccarelli’s inconsistent analyses pertaining to the findings of various studies in the literature, as well as the shut down of other experts’ opinions that are partially based upon Dr. Baccarelli’s analysis, might be reasonable, her arguments regarding the role of genetics not being controlled for in the literature are not reasonable -and for one major, stupendous reason: she relied upon Bai et al. (2019).

Genetic Confounds Part 1: Bai et al. (2019), My Old Nemesis

District Judge Denise Cote, in her 148 page opinion, does not provide a citation for her statements regarding genetic heritability of autism being at 80%, which she draws upon for her arguments against the plaintiffs. However, to my knowledge, Bai et al. (2019) is the only study that draws such a conclusion [15].

I previously wrote a commentary on this study whose methods, limitations, and lack of control for various confounds are astoundingly concerning, doing so at a time when I was a worse writer than I am now.

See below.

To summarize my criticism of Bai et al: the study only controlled for birth year and sex in their analysis, there was no adjustment for other environmental factors associated with autism known at the time of their study, their methods claimed to control for shared environments but the authors admitted two types of misspecification as limitations to their study, this misspecification -I argue- is augmented by the fact that the study barely controlled for any confounds, ‘genetically induced correlation’ is used to ascertain environmental effects and maternal effects rather than assessing them through other means (e.g., medical records, surveys, lab tests, etc.), the primary analysis focused on the Danish, Finnish, and Swedish samples, which are predominantly White/Caucasian regions, thus, bringing into question the generalizability of the findings to other ethnic groups, and this is highly important because, per the latest CDC publication in 2023, autism prevalence for the first time was higher among Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander children. Together, all of these flaws tarnish the credibility of the findings of the study.

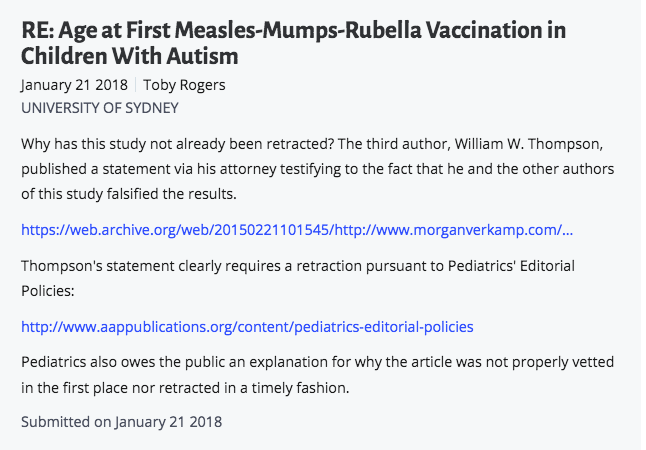

Ethnicity is particularly interesting in light of the CDC’s publication in 2023 regarding autism incidence. More people are now educated on the fraud of DeStefano (2004), a study conducted by the CDC on the MMR vaccine and autism, which omitted African American children from the sample who did not possess a valid State of Georgia birth certificate, veiling a previous significant statistical finding between MMR and autism that resulted in a publication that reported a ‘no association’ finding to the public. This has been quite the drama for Dr. Brian Hooker, who received calls from a CDC scientist who co-authored the study confessing to the omission of data, and who later conducted a reanalysis of the data and found a 3.86x Odds of Autism in African American Boys. How relevant are the findings of Bai et al. (2019) within this contextual framework?

Worst of all is the limitation of misspecification due reliance of the assumption of independence between genes and environment.

“The first potential misspecification arises from the possible violation of the assumption of independence between genetic and environment. If this correlation is not specifically included in the model, its components will mostly be incorporated into the estimate of genetic variance component, potentially biasing the heritability estimate.”

Bai et al. (2019)

Genes and environment always interact. There is now new research published regarding gene-metal interactions in their relation to autism [13, 14]. But wasn’t this obvious before hand? So the Bai et al. authors admit misspecification is a limitation to their study that may specifically result in biases toward genetic heritability estimates.

Judge Cote’s use of Bai et al (2019) in her argument against a lack of control for genetic confounds is undermined by the various issues with the study.

Now, let us move on to additional problems with Bai et al. (2019)…

I did not discuss in my original commentary the ‘Disclaimer’ and ‘Conflict of Interest Disclosures’ listed in the study itself, and perhaps now is a good time to do so as they are cause for grave concern because they further undermine Judge Cote’s reliance on Bai et al. (2019) in her argument regarding genetic heritability and her dismissal of Dr. Baccarelli and other expert opinions.

Disclaimer

“The study data from Israel were obtained from the Ministry of the Interior and Ministry of Health and were analyzed in Israel, and the results may or may not reflect the views of these ministries.“

bai et al.(2019)

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

- Dr. Windham reported receiving grants from NIH sub-contract during the conduct of the study.

- Dr. Sourander reported receiving grants from Academy of Finland Flagship Programme (decision No. 320162), Academy of Finland (decision No. 308552), the National Institutes of Health (NIH; W81XWH-17-1-0566 ), and the NIH (1U01HD073978-01) during the conduct of the study.

- Dr. Francis reported receiving grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke during the conduct of the study.

- Ms. Yoffe reported employment with the Israeli Ministry of Health, which did not fund the current research.

- Dr. Leonard reported being a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow.

- Dr. Buxbaum reported receiving grants from the Seaver Foundation during the conduct of the study.

- Dr. Wong reported receiving grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study and grants from NHMRC outside the submitted work.

- Dr. Breshnahan reported receiving grants from Columbia University during the conduct of the study.

- Dr. Levine reported receiving research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the current research more than 3 years ago.

- Dr. Sandin reported receiving grants from NIH during the conduct of the study.

- Dr. Sandin reported being a Faculty Fellow of the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation.

No other disclosures were reported.”

I mean, I would hope not after this laundry list they just went through.

To what extent are the study’s methods and analysis, -at best, without even controlling for a number of confounds associated with autism; at worst, questioning whether the study’s methods and analyses even possesses construct and content validity- influenced by these conflict of interests?

In summary, Judge Denise Cote’s reliance on Bai et al. (2019) for claims regarding a lack of control for genetic confounds in the acetaminophen-autism literature because of 80% genetic heritability claims is moot; the study she relies upon, conversely, does not control for multiple environmental factors known to be associated with autism (i.e., their statistical analyses that claim to do so are, in my opinion, subject to scrutiny regarding construct validity), many of which are controlled for in the acetaminophen literature. It saddens me to say that this atrocious study has been used by multiple organizations to inform the public about autism risk -I’m looking at you Autism Speaks [16].

Additionally, it would be worthwhile to educate Judge Cote on the findings by Hallmayer et al.’s (2011) twin study on autism, which found genetic factors only accounted for a maximum of 38% of heritability [17], as well as the findings by the Frazier et al. (2014) twin study that found environmental effects accounted for 64-78% heritability [20]. It is worth noting, however, that within various studies on the genetic versus shared environment contribution toward autism there is debate regarding -surprise surprise- using autism symptoms as outcome measures versus autism diagnostic criteria. To my knowledge, the literature is ongoing, and researchers are continuing to fine tune their investigations. It is worth noting, that Hallmayer et al. (2011), although also not adjusting for various covariates I would’ve liked to have seen, provided some additional strength to their study by excluding twins with a history of neurogenetic conditions that might account for autism (eg, fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and neurofibromatosis). Bai et al. did not make such adjustments, although, to be fair, neither did Frazier et al. (2014).

Thus, to rely soley on Bai et al. (2019) as Judge Cote has done, is not to do justice to a developing literature on genetic contributions toward autism versus environmental contributions. Is she guilty of cherry picking, as she has accused Dr. Baccarelli? Other research certainly does not claim such high genetic heritability.

Finally, let us assume for a moment that the findings of Bai et al. (2019) are credible. Perhaps we accept that genetic heritability can contribute toward 80% risk of autism. Even so, Judge Cote herself notes on page 13 of her opinion that only about 15% of cases of autism are associated with a genetic mutation, as well as acknowledges that not all individuals with that genetic mutation will develop autism.

The precise cause of ASD is unknown. Heritability, a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK. Acetaminophen – ASD-ADHD Products. Denise cote, district judge. Page 13

measure of how much variation in a trait at the population level is due to genetic influence, rather than environmental factors, is estimated to be about 80%. Id. at 64. About 15% of ASD cases appear to be associated with a known genetic mutation. Id. Even when a known genetic mutation is associated with ASD, not all individuals with that genetic mutation will have ASD.

So, what are the contributing factors to 85% of other autism cases, if an 80% genetic influence only accounts for 15% of autism cases associated with genetic mutation? Her statement is in line with recent literature review on gene-environment interactions discussing autism genetic causes accounting for only 10-30% of autism cases [18]. However, this leaves anywhere from 70-90% of autism cases being unaccounted for by genetic influence. Perhaps there are other factors that may contribute toward those autism cases, acetaminophen being one of them.

Genetic Confounds Part 2: the Stergiakouli Study

The study on ADHD and acetaminophen by Stergiakouli, Thapar, & Smith (2016) did control for genetic influence on ADHD, and found that the association between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and childhood behavioral problems could not be explained by genetic risk [7].

“…an index of ADHD genetic risk in the mothers was not associated with acetaminophen use during pregnancy. These findings, when coupled with those from the previous discordant sibling design study, suggest that the association between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and childhood behavioral problems is not explained by unmeasured familial factors linked to both acetaminophen use and childhood behavioral problems and that the findings are consistent with an intrauterine effect. Our results could have important implications for public health advice, which currently considers acetaminophen safe to use during pregnancy.”

Stergiakouli, Thapar, & Smith (2016)

This study was not independently addressed in Judge Cote’s opinion. Did she ignore it? It was included in the meta analysis by Masarwa et al. (2018), which is discussed various times in her opinion. Why wasn’t this study part of her opinion in addressing genetic confounds?

Interestingly, the Stergiakouli study aimed to assess ADHD, but the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire used as the outcome measure could perhaps be argued to fit better with the autism diagnostic criteria. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire used in their study assesses 5 domains: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity symptoms, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviors. Under DSM-5 criteria for autism, ’emotional symptoms,’ ‘peer relationship problems,’ and ‘prosocial behaviors’ could be argued to fall under A.1. of the diagnostic criteria.

“Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.”

Diagnostic Criteria for 299.00 Autism Spectrum Disorder. DSM-5, A.1.

Additionally, area A.3. of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism is worth considering as well.

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Diagnostic Criteria for 299.00 Autism Spectrum Disorder. DSM-5, A.3.

This is one of the advantages, I would argue, of relying on outcome measures that assess symptoms rather than diagnostic criteria. Although unintentional, the findings of the study are perhaps also applicable, and maybe even more so, to autism. But, of course, this makes litigation and healthcare decision making more difficult when conditions are difficult to parse and researchers themselves don’t address these overlaps -not to mention, accidentally use outcome measures that might fit autism better than ADHD. There is no mention of the word ‘autism’ or ‘ASD’ in their study.

Nevertheless, the control for genetic confounds conducted by this study, whether it is regarding autism or ADHD symptoms, appears to have been ignored in Judge Cote’s opinion. I do not know if Dr. Baccarelli or other experts referenced the study in their analysis, but they had to have referenced it because was part of the meta analysis by Masarwa et al.(2018).

Why wasn’t this study included in Judge Cote’s analysis of the control for genetic confounds?

Stergiakouli et al. additionally adjusts for: maternal age at birth, parity, socioeconomic status, smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy, prepregnancy body mass index, maternal self-reported psychiatric illness, possible indications for acetaminophen use, smoking, alcohol consumption, muscle and joint problems, infections, migraine, or headaches in the previous 3 months.

Altogether, these adjustments provide strong evidence against confounding by indication, and perhaps strong causal evidence for the association between acetaminophen and autism.

Adjusted Covariates

For personal reference, I began to compile a list of the various covariates adjusted for in the autism-acetaminophen literature. Consider the list below preliminary, as everything below will be double checked for a later publication of a public-friendly literature review on acetaminophen and autism.

Numbers next to a covariate indicate that the study adjusted for them in their analysis. Khan et al. (2022) provides a nice review of the literature with all of the covariates [9], but doesn’t include the Woodbury et al. (2023) study which was just published last month [8].

- Maternal age at delivery [1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]

- Education [1, 3, 4, 5, 8]

- Body-mass index (BMI) [1, 3, 4, 7]

- Alcohol [1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]

- Smoking [1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8,]

- Mental health problems during pregnancy [1, 6]

- Gestational age at birth [1, 2, 5]

- Parity [1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8]

- Maternal fever [1, 2, 3, 5, 6,]

- Headache or migraine [3, 6, 7,]

- Infections during pregnancy [1, 3, 6, 7]

- Pelvic girdle pain [3]

- Back pain [3, 6]

- Neck pain [3]

- Maternal depressive symptoms [3, 6, 8]

- Maternal socioeconomic status[2, 7],

- Stress/Psychological distress during pregnancy [4, 8],

- Maternal social class [5]

- Household income [8]

- Latitude of country or region [2, 3]

- NOS score [2]

- Duration of exposure to acetaminophen [2]

- Marital status or cohabiting [3, 4]

- Folic acid use during pregnancy [3]

- Abdominal pain and other pain [3]

- Concomitant medications: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [3, 6], antiepileptics (N03A) [3, 6], antidepressants (N06A) [3, 6], opioids (N02A) [3, 6], triptans (N02CC), [3, 6] and benzodiazepines (N05CD and N05BA) [3, 6], antipsychotics (N05A) [6], and other analgesics (N02CA and N02CX) [6]

- Maternal race/ethnicity [4]

- Delivery type [4]

- Preterm birth [4, 5]

- Low birth weight [4]

- Child gender [1, 5]

- Age at testing [5]

- IQ [5]

- Any chronic illness [5]

- Urinary tract infection-not necessarily related to acetaminophen use-during pregnancy [5]

- Years between pregnancies [6]

- Maternal self-reported psychiatric illness [7]

- Possible indications for acetaminophen use [7]

- Muscle and joint problems [7]

- Genetic confounder for ADHD [7]

- Whether the participant’s native language was English [8]

- Child at at assessment [8]

- Number of older siblings [8]

- Mean Perceived Stress Score [8]

Quite the list of covariates that build a strong causal relationship, in my opinion.

Synergistic Toxicity, the Elephant in the Autism Epidemic

If I were to summarize my current understanding of the autism literature, it is as follows: major factors associated with autism are not adjusted against one another in the literature as confounders. What is their cumulative synergistic-toxicity?

Research questions: to what degree is the relationship between prenatal acetaminophen and autism in the offspring impacted by prenatal vaccines? Did the mother have to take Tylenol due to an averse reaction to a vaccine? Where does the mother live, in an area with air pollution or pesticides? How do each of these impact her health and create additional covariates? Did she have a previous history of threatened abortion, or abortion, that we need to adjust for as a covariate in the acetaminophen-autism literature? To my knowledge, this last one hasn’t been done, and its an important one.

Similarly, within the domain of genetics, to what degree are genetic influences diminished by controlling for known environmental factors associated with autism? Bai et al. and other studies referenced claim to conduct analyses to ascertain environmental influences without collecting data on them (per my current understanding); and I don’t understand exactly why they don’t collect data on additional factors associated with autism to adjust for them. Too expensive? Too time consuming? At this point, given the rising incidence of autism, I think it’s necessary to not leave anything off the table.

Thus, the impact of multiple factors associated with autism during and after pregnancy is a ghost that haunts me. The problem of confounding becomes bigger the greater number of factors are associated with autism; and the greater the number of factors, the more difficult it is to hold people accountable when their product/company/whatever may be contributing to neurodevelopmental problems.

While I understand the frustration of of many law firms seeking accountability for the condition of children that has impacted the lives of many families, the question going through my head is: how do you know acetaminophen alone caused that child’s autism?

And I only have one idea right now to try to answer that question…

Rule Out Other Factors: Case by Case

If I were a lawyer building a case for a child, the first way I could think to strengthen my case is to rule out all other factors associated with that child’s diagnosis. A questionnaire. Did the mother take vaccines during pregnancy? Was she exposed to pesticides prenatally? Did she live in a high pollution area? Is the child’s toxic heavy metal burden accounted for? Did the mother have a previous history of abortion or threatened abortion? Etc. This would help in building individual, stronger cases for the causality in prenatal acetaminophen exposure and an autism diagnosis, in my view.

There is still a lot to unpack regarding the contribution of multiple factors in an autism diagnosis: is minor contribution toward a diagnosis such as autism enough to hold a company accountable, even if that factor alone did not contribute to the child’s autism? What if a pregnant mother took excessive acetaminophen, but also received multiple vaccines during pregnancy that further exacerbated the situation? Is the contribution of acetaminophen toward a child’s diagnosis enough to hold them accountable for warning people about its use during pregnancy?

Regressive autism within a week or less of a vaccine is probably the most causal relationship that we presently can argue. It might be argued that autism regression after a vaccine is indicative of the vaccines’ heavy impact in spite of other environmental factors associated with autism the child may have been exposed to (e.g., pesticides, air pollution, etc.) -and there are plenty of parents everywhere providing anecdotal cases.

Ultimately, as we continue to move forward, I am hopeful that together, and by holding more conversations about the autism research, we can push for more answers, we can push for more public awareness, and we can push for more push for research that brings us closer toward understanding autism.

My Story: Why I Care

I previously shared in my commentary on Dr. Huberman’s episode about autism with Dr. Karen Parker a few things about myself: speech delays as an infant, minor behavioral problems, academic problems, emotional development problems, and a few other things. I totally forgot to mention in that commentary that my mom said I also had seizures my first few months of life. I don’t identify as having autism, or as being “neurodivergent,” as I think it causes problems and attempts to normalize a difficult life condition many children, adults with autism, and parents live with.

Now as an adult, I work as a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) for a major ABA services provider -primarily services for young children with autism, although I occasionally receive teenagers as well. I love the work that I do; it’s very fulfilling to see the progress children and parents make. I also happen to supervise various adults on the autism spectrum employed with the company who provide 1:1 ABA services themselves -and I can think of at least two who are extremely good at what they do. So, there are adults with a diagnosis of autism working in ABA helping children with autism. Life is amazing like that.

Primarily, it is because of what I witness in my line of work, the struggles, the tantrums, the parental frustration, the eventual successes…that I wanted to do something positive, such as starting this library, to help the field of autism outside of my regular line of work.

Sometimes it feels like my job is in putting out fires…meanwhile gasoline is being poured all around me as the incidence of autism continues to rise and it feels like there’s not enough public awareness to stop it from happening.

How much am I doing to prevent autism?

More, I want to do more.

Hence, this library (undergoing refurbishment and planning).

All the best,

Autism Librarian 🙂

References

- Alemany, S., Avella-García, C., Liew, Z. et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to acetaminophen in relation to autism spectrum and attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms in childhood: Meta-analysis in six European population-based cohorts. Eur J Epidemiol 36, 993–1004 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00754-4

- Reem Masarwa, Hagai Levine, Einat Gorelik, Shimon Reif, Amichai Perlman, Ilan Matok, Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Cohort Studies, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 187, Issue 8, August 2018, Pages 1817–1827, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy086

- Vlenterie, R., Wood, M. E., Brandlistuen, R. E., Roeleveld, N., van Gelder, M. M., & Nordeng, H. (2016). Neurodevelopmental problems at 18 months among children exposed to paracetamol in utero: a propensity score matched cohort study. International journal of epidemiology, 45(6), 1998–2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw192

- Ji, Y., Azuine, R. E., Zhang, Y., Hou, W., Hong, X., Wang, G., Riley, A., Pearson, C., Zuckerman, B., & Wang, X. (2020). Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood. JAMA psychiatry, 77(2), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3259

- Claudia B Avella-Garcia, Jordi Julvez, Joan Fortuny, Cristina Rebordosa, Raquel García-Esteban, Isolina Riaño Galán, Adonina Tardón, Clara L Rodríguez-Bernal, Carmen Iñiguez, Ainara Andiarena, Loreto Santa-Marina, Jordi Sunyer, Acetaminophen use in pregnancy and neurodevelopment: attention function and autism spectrum symptoms, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 45, Issue 6, December 2016, Pages 1987–1996, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw115

- Brandlistuen, R. E., Ystrom, E., Nulman, I., Koren, G., & Nordeng, H. (2013). Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. International journal of epidemiology, 42(6), 1702–1713. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt183

- Stergiakouli, E., Thapar, A., & Davey Smith, G. (2016). Association of Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy With Behavioral Problems in Childhood: Evidence Against Confounding. JAMA pediatrics, 170(10), 964–970. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1775

- Woodbury, M. L., Cintora, P., Ng, S., Hadley, P. A., & Schantz, S. L. (2023). Examining the relationship of acetaminophen use during pregnancy with early language development in children. Pediatric research, 10.1038/s41390-023-02924-4. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02924-4

- Khan, F. Y., Kabiraj, G., Ahmed, M. A., Adam, M., Mannuru, S. P., Ramesh, V., Shahzad, A., Chaduvula, P., & Khan, S. (2022). A Systematic Review of the Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Acetaminophen: A Mystery to Resolve. Cureus, 14(7), e26995. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26995

- Denisova, K., & Lin, Z. (2023). The importance of low IQ to early diagnosis of autism. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 16(1), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2842

- Liew, Z., Ritz, B., Virk, J., Arah, O. A., & Olsen, J. (2016). Prenatal Use of Acetaminophen and Child IQ: A Danish Cohort Study. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 27(6), 912–918. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000540

- Laue, H. E., Cassoulet, R., Abdelouahab, N., Serme-Gbedo, Y. K., Desautels, A. S., Brennan, K. J. M., Bellenger, J. P., Burris, H. H., Coull, B. A., Weisskopf, M. G., Takser, L., & Baccarelli, A. A. (2019). Association Between Meconium Acetaminophen and Childhood Neurocognitive Development in GESTE, a Canadian Cohort Study. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology, 167(1), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfy222

- Rahbar, M. H., Samms-Vaughan, M., Saroukhani, S., Bressler, J., Hessabi, M., Grove, M. L., Shakspeare-Pellington, S., Loveland, K. A., Beecher, C., & McLaughlin, W. (2021). Associations of Metabolic Genes (GSTT1, GSTP1, GSTM1) and Blood Mercury Concentrations Differ in Jamaican Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041377

- Rahbar, M. H., Samms-Vaughan, M., Saroukhani, S., Lee, M., Zhang, J., Bressler, J., Hessabi, M., Shakespeare-Pellington, S., Grove, M. L., & Loveland, K. A. (2021). Interaction of Blood Manganese Concentrations with GSTT1 in Relation to Autism Spectrum Disorder in Jamaican Children. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 51(6), 1953–1965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04677-z

- Bai, D., Yip, B. H. K., Windham, G. C., Sourander, A., Francis, R., Yoffe, R., Glasson, E., Mahjani, B., Suominen, A., Leonard, H., Gissler, M., Buxbaum, J. D., Wong, K., Schendel, D., Kodesh, A., Breshnahan, M., Levine, S. Z., Parner, E. T., Hansen, S. N., Hultman, C., … Sandin, S. (2019). Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort. JAMA psychiatry, 76(10), 1035–1043. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1411

- Is Autism Genetic? Study Finds 80% Risk From Inherited Genes. https://www.autismspeaks.org/science-news/autism-genetic-study-finds-80-risk-inherited-genes

- Hallmayer, J., Cleveland, S., Torres, A., Phillips, J., Cohen, B., Torigoe, T., Miller, J., Fedele, A., Collins, J., Smith, K., Lotspeich, L., Croen, L. A., Ozonoff, S., Lajonchere, C., Grether, J. K., & Risch, N. (2011). Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Archives of general psychiatry, 68(11), 1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76

- Keil-Stietz, K., & Lein, P. J. (2023). Gene×environment interactions in autism spectrum disorders. Current topics in developmental biology, 152, 221–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2022.11.001

- Sandin, S., Lichtenstein, P., Kuja-Halkola, R., Larsson, H., Hultman, C. M., & Reichenberg, A. (2014). The familial risk of autism. JAMA, 311(17), 1770–1777. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.4144

- Frazier, T. W., Thompson, L., Youngstrom, E. A., Law, P., Hardan, A. Y., Eng, C., & Morris, N. (2014). A twin study of heritable and shared environmental contributions to autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 44(8), 2013–2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2081-2